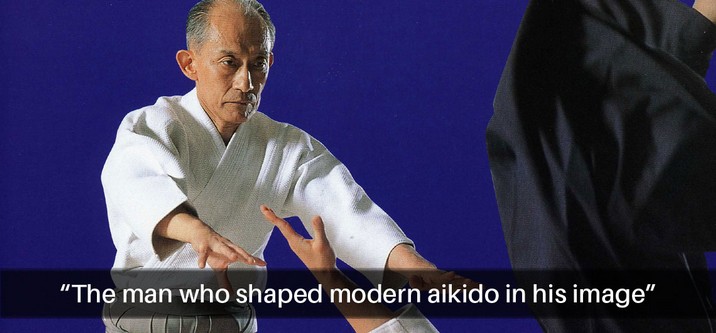

The man who shaped modern aikido in his image

In the Aikikai system, today’s world of aikido bears the stamp of Second Doshu Kisshomaru Ueshiba more than any other person. There is no other figure who has been more influential, not even the Founder Morihei Ueshiba himself. I realize that, for many of the aikido faithful, this will be a controversail statement. Allow me to elaborate.

First of all, aikido is a post-World War II phenomenon. Morihei Ueshiba and his fledgling martial art were known primarily in martial arts circles, not by the general public, prior to the war. What has become aikido today has been shaped primarily by the Ueshiba family through the auspices of the Aikikai Hombu Dojo system after 1955.

The arbiter of this process of dissemination and the content of Aikikai aikido is none other than Kisshomaru Ueshiba, the Founder’s son. In 1942, Kisshomaru assumed operational control of what would become the Aikikai at the tender age of 21. Morihei had retired to Iwama, World War II raged, and Tokyo would soon be bombed. Kisshomaru was thrust into a leadership position for which he was ill-equipped while a university student. He would continue uninterrupted as head of the Aikikai, the world’s largest aikido organization, until his passing in 1999.

The Aikikai was barely functioning as an entity after the war until around 1955. During that period, Kisshomaru was simply attempting to hold the remnants of the aikido structure together until better times, without much thought to the future direction of the art. In fact, he was obliged to hold down a full-time job in a securities firm to support himself and the rundown Aikikai dojo.

Later on, as aikido began to gather some attention among the general public, it was Kisshomaru, in consultation with a group of elders and peers, who gradually began shaping the policies that would lead to a steady, if not spectacular, growth of aikido.

The Aikikai adopted a series of measures starting in the late 1950s that would soon ensure its success. This included the establishment of a growing network of branch dojos, and aikido clubs in universities and businesses all over Japan. Furthermore, the Aikikai dispatched a stream of Japanese instructors loyal to the mother organization to key locations in major foreign countries. Many of them in turn created large aikido organizations abroad.

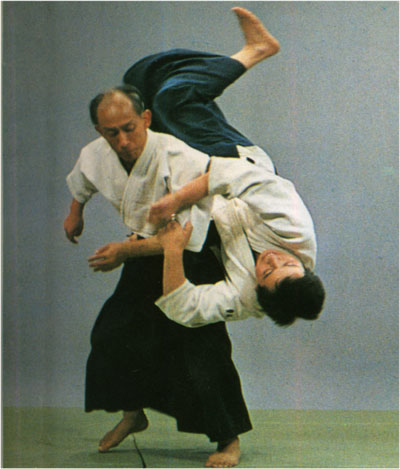

In a technical sense, during the 1950s through 1974, Kisshomaru’s and Koichi Tohei’s methodologies were dominant at the Aikikai Hombu Dojo. For many years they worked in tandem to shape the curriculum of the headquarters school. Tohei had a strong influence with his stress on “ki principles”, but otherwise there was considerable overlap in the techniques taught and the two approaches were compatible. Moreover, the two published a series of books in the early 1960s that appeared in English and other European languages. These works presented a technical and theoretical framework of aikido to a worldwide audience and reaffirmed the position of the Aikikai as the central authority of the art.

Although a larger-than-life figure in many ways, Morihei Ueshiba’s postwar role was primarily symbolic, and he was not a decision-maker in the affairs of the Aikikai. O-Sensei was rather irascible by nature and often critical of Aikikai teaching practices. Consequently, he was largely marginalized and encouraged to absent himself from the Hombu. He spent much of his time traveling to meet with friends and students, and at his country home in Iwama. In this way, he would be less of an impediment to the smooth operation of the dojo.

Let’s fast-forward several decades later and turn our eyes to the present state of the art. Obviously, I am focusing on the Aikikai worldwide network which dwarfs the many smaller aikido organizations that exist in size and influence.

Taken collectively, the Aikikai organization consists of several tens of thousands of schools spread over all but the smallest countries of the globe. To my knowledge, no accurate survey of actual numbers exists, but let us adopt the arbitrary figure of one to two million practitioners to give an idea of the art’s scope.

The curriculum followed in these schools is largely based on Kisshomaru Ueshiba’s many technical books issued over a 40-year period. Most were published by Kodansha, Ltd., Japan’s largest publishing firm, in Japanese and English, and various European languages. Kisshomaru’s son, the present Doshu Moriteru Ueshiba, has continued the unabated production of similar books starting even before his father’s death.

The administrative policies of the Aikikai were formulated and fine-tuned by Kisshomaru and his advisers over the years. This includes the dan ranking procedures and accompanying fee structures which constitute the main revenue stream of the organization.

In the 1980s and 90s, Kisshomaru developed an accommodating stance toward the acceptance of outside organizations into the Aikikai fold. This included the re-integration of groups that had earlier split with the Aikikai at the time of the resignation of Koichi Tohei in 1974. This is a policy for which he has been justifiably praised.

Another sphere of influence in which Kisshomaru was dominant is the shaping of the image of his father, Morihei Ueshiba, for general consumption. Through his widely read biography of Morihei titled in English, “A Life in Aikido,” Kisshomaru set forth an official version of the early history of aikido that has been used as the primary source by many later writers.

Furthermore, Kisshomaru recast O-Sensei’s spiritual vision in a language that was accessible to modern Japanese and an international reading audience. This was accomplished by expunging most of the esoteric Shinto imagery that Morihei used in his speeches and lectures. Again, the vehicle was a series of books on Morihei’s aikido philosophy published by Kodansha. In some cases, authorship was even attributed to Morihei himself. Professor John Stevens has translated and edited most of these publications in English.

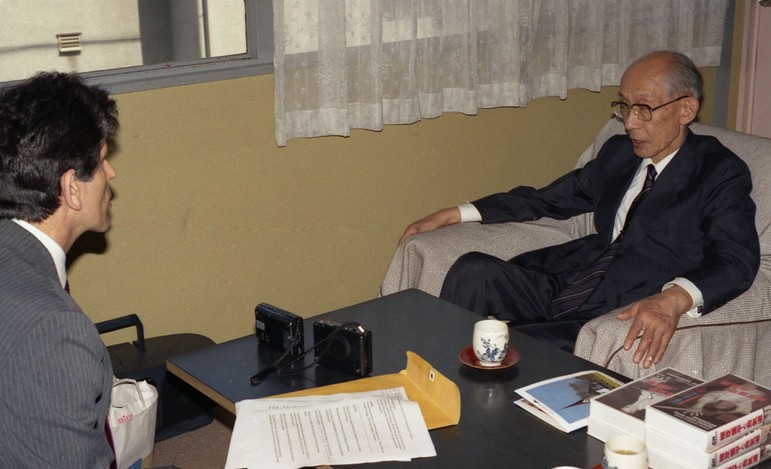

I recall vividly meeting Kisshomaru Ueshiba in 1963 in Los Angeles on his first visit to the USA. At that time, he was a bespectacled 42 year old, with a quiet and unassuming manner. He taught and demonstrated in a matter-of-fact way with little explanation. Nothing about him was flamboyant or overstated.

I had periodical contact with Kisshomaru over the next 36 years and interviewed him on more than ten occasions. I watched him transform into a dignified, paternal figure. This process accelerated notably after the departure of Koichi Tohei from the Aikikai in 1974. Kisshomaru became an object of reverence, always to be accompanied by a doting entourage. This august mantle was inherited by his son and present Doshu, Moriteru Ueshiba, and will no doubt be passed in due course to his son Mitsuteru.